HBO true crime series Last Call feels like a response to the media’s portrayal of queer killers

The lives of victims in New York’s queer community are the focus of HBO true crime miniseries Last Call. This approach is true crime done right, writes Amelia Berry, building a powerful story of love, loss, community, and resilience out of a series of brutal, cruel killings.

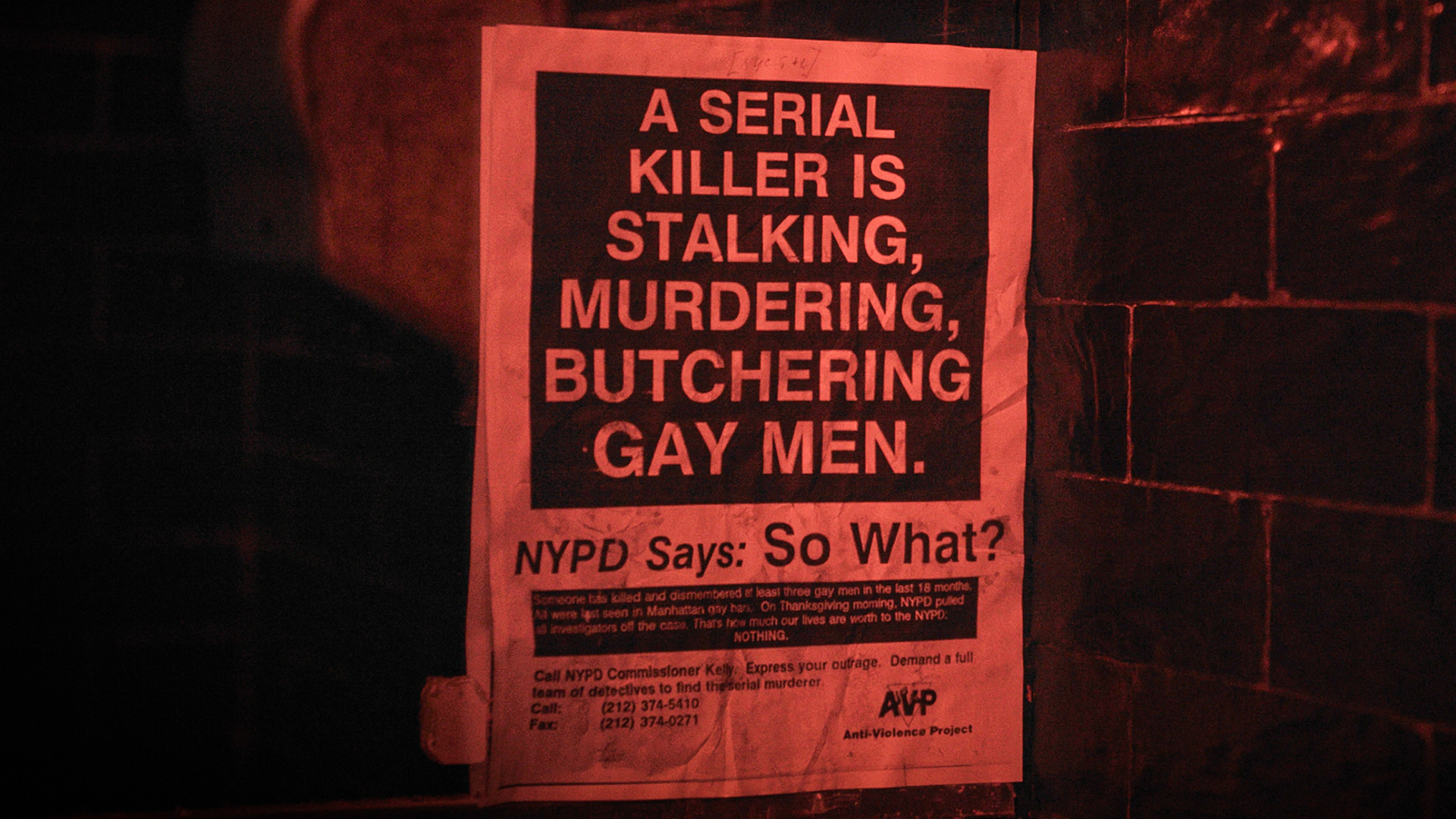

New York, 1991. The queer community is ravaged by the AIDS crisis, dehumanised by the press, and demonised by the political establishment. Now, they face a rising tide of street violence. At best, the NYPD is reluctant to help—at worst, they themselves are the perpetrators. At the same time, queer culture is flourishing—catalysed by political resistance and blossoming into music, art, dance, literature, parties.

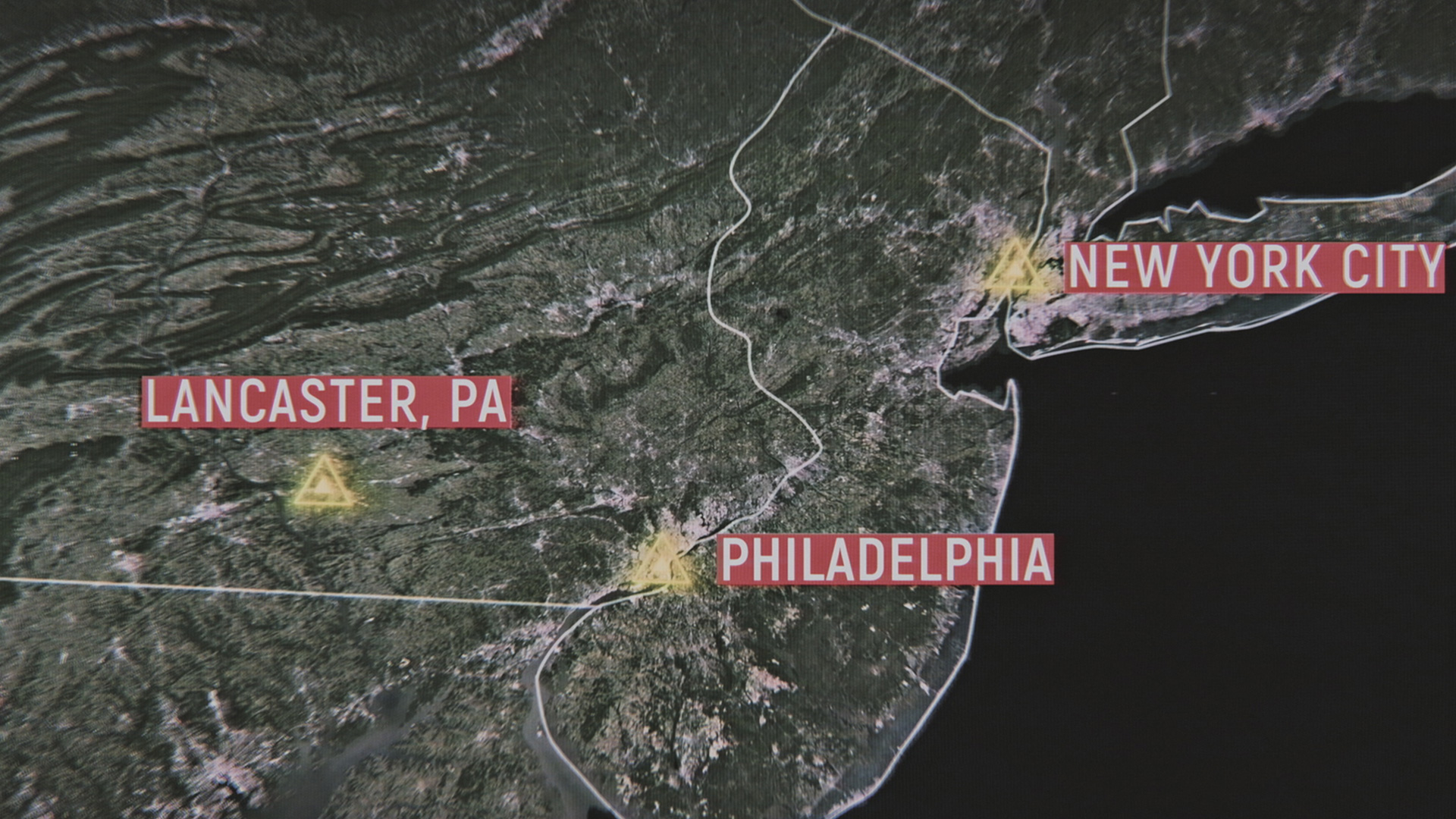

This is the backdrop to Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York, a new HBO true crime miniseries directed by Anthony Caronna (the documentarian behind Susanne Bartsch: On Top). Based on Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York by Elon Green, it maps the murders of serial killer Richard Rogers who drugged, murdered, and dismembered gay men in New York throughout the early 90s and with links to deaths through the two decades prior.

While ‘true crime’ as a label increasingly conjures up a kind of lurid fetishisation of fear and murder (did you know Ted Bundy has a ‘fandom’? Have you seen a ‘Ted Bundy Fancam’?), Last Call is something quite different. There’s no lionisation of law enforcement, no credulous awe of spurious forensic technology, and really very little attention paid to the actual killer—only the final episode is dedicated to his capture and trial.

Instead, Last Call focuses on the lives of the victims. Each episode is named for the men killed, and is filled with interviews with their families, friends, and loved ones. It’s also a show that cares deeply about the communities and political context that these men were a part of, featuring extensive interviews with activist and Gay USA host Andy Humm, and advocates from New York queer anti-violence organisations.

This approach was something that Caronna and producer Howard Gertler took very seriously.

“[We didn’t want] to create something that would re-traumatise the family members of the victims. The community at large would have to guide how we were going to approach the violence of it,” Gertler told Indiewire.

“We came at it with not wanting to necessarily focus on [the perpetrator] and to let the queer community speak for itself and drive the narrative of the entire series…. So by the time we get to four, we’re seeing who Richard Rogers is through the lens of all these people that have just wanted to see him caught,” Caronna added, “He was just never the thing that we wanted to focus on. I never really had a great interest, personally, in focusing on the perpetrator.”

An interesting product of this is how starkly Last Call speaks to the ways attitudes to queerness and homosexuality have changed—and the ways in which they haven’t. In the family interviews there is sometimes discomfort or denial of these men’s sexuality. One victim’s nephew has himself been disowned for his queerness. Activists and friends speak directly to the growing tide of anti-queer (and particularly anti-trans) backlash we’re experiencing right now.

The police come across particularly badly. In interviews, the officers seem constantly perplexed by the focus on sexuality, claiming again and again that the victim being a gay man was totally inconsequential to the case—“I don’t know anything about where all the gay bars in New York are. I don’t know anything about the community. It really is irrelevant. I mean we don’t… all we do… All we know is we got a body and we gotta find out who would do it… but it’s not really relevant to anything.”

It would be laughable if it wasn’t so infuriating. Police often failed to follow up at the gay piano bars where the men were picked up, apparently too uncomfortable to talk to the patrons or staff. With the dismembered bodies being dumped in neighbouring states, the NYPD flat out refused to be involved for a long time and we see plenty of evidence of their open hostility to the queer community.

The news media don’t come across much better, printing insulting and dehumanising obituaries (“Anthony Morrero: Crack Addict, Prostitute”), and coming up with various patronising and catchy names for the killer—the ‘gay slay’ killer, and of course the Last Call Killer.

Of Richard Rogers himself we learn a little. Not caught until fingerprint databases were consolidated in the early 2000s, he was a man who had already literally gotten away with murder in the early 70s, acquitted of his admitted killing of housemate Fredric Spencer on a ‘gay panic’ defence.

It’s difficult to say that any true crime documentary series is ‘important’, but Last Call certainly comes close. It’s tense, cathartic, and intimately personal—a portrait of a community in crisis, but a community organising itself to fight back. It offers sympathy and humanity to groups like sex workers and closeted married men that are often demonised, even within the queer community.

Ultimately, it feels like an answer to so much of the media that portrays queer killers. It’s hard to imagine any telling of Jeffrey Dahmer’s story that isn’t totally dedicated to psychologising and mythologising the man himself. Films like Cruising (Based on Arthur Bell’s reporting on a series of unsolved killings in the gay leather community) take queerness as something alien, an exotic backdrop for an already sensationalised subject.

People will always be fascinated by tragedy, by violence, by the peculiar evil of the serial killer. They’ll always be fascinated by true crime. Last Call shows true crime done right, building a powerful story of love, loss, community, and resilience out of this series of brutal, cruel killings. Whether you’re a murder podcast fan or you’re just interested in the history of queer culture, queer love, and queer death—this is essential, heartbreaking viewing.