Lost 70s George Romero film The Amusement Park is vicious satire

“Indignant, thoroughly cynical and deliberately upsetting” – and now streaming nearly 50 years later.

George A. Romero’s rediscovered “lost” film The Amusement Park, remastered 46 years after its completion, confronts society’s mistreatment of the elderly – more horrifically than its Lutheran funders intended. Clearly, Romero, armed with a wad of church cash, did not come to fuck around, writes Aaron Yap.

More than a curious footnote in George A. Romero’s career, The Amusement Park should be a discovery valued in the same breadth as Orson Welles’ once-lost The Other Side of the Wind—a significant missing piece of a master filmmaker’s wholly distinctive oeuvre. Commissioned in 1973 by the Lutheran Service Society to confront society’s mistreatment of the elderly, the resulting work so perturbed the faith-based organisation that they shelved it from the public eye before a print resurfaced in 2018.

See also:

* All new streaming movies & series

* Movies now playing in cinemas

Now streaming exclusively on Shudder, the 4K restoration—by film preservation outfit IndieCollect, under the guidance of Romero’s wife Suzanne Desrocher-Romero—reveals a key provocation in his slightly wobbly post-Night of the Living Dead period. It’s a blunt-force PSA that reinforces his voice as a vicious satirist of class, culture and capitalism: indignant, thoroughly cynical and deliberately upsetting.

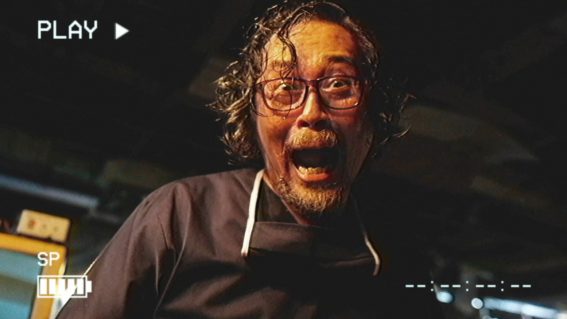

The film’s mission statement to condemn our widespread rejection of old age is laid bare in the opening moments, where 71-year-old actor Lincoln Maazel (Martin) addresses the audience with Welles-like authority. “Remember when you watch the film, one day you will be old,” Maazel cautions.

Next we see him, dapper in a white suit, entering a surreally white room. Another elderly man sits there, shaken, face bloodied and bruised. He wears a similarly white suit but it is stained. Maazel asks if the man wants to come out to the park. “There’s nothing outside”, the man tells him in a trembling, panting voice fraught with despair.

The ensuing 53 minutes is a punishingly sustained critique, an act of social rage, wielding the bustling grounds of the titular purgatorial park as an allegory of a bitterly self-absorbed world that devalues the elderly at every turn. There’s little room for polished storytelling: The Amusement Park tumbles out of the gate into a series of disorienting episodes, dragging the progressively battered Maazel through a vortex of endless, humiliating discrimination.

Rides require extensive checks on income levels, mental state and health—factors that by default put seniors at a disadvantage. Maazel is pushed aside, jeered at, called a “degenerate”, and robbed and clobbered by a biker gang without assistance from passers-by. The park’s freak show attraction is simply a parade of elderly people. Romero is remorseless, messy, his agitated editing and Bill Hinzman’s restless, roving camerawork ramping up the Twilight Zone-ish nightmare atmosphere to a level that’s nearly one hysterical burst of sermonising away from a Ron Ormond scare flick.

Beneath the anger, Romero locates the terrible, melancholy loneliness of it all. The film peaks with a one-two punch of some of Romero’s most crushing, horrific visions: a fortune teller’s prediction of a young couple’s future trades hope and happiness with overwhelming psychic disrepair and welfare neglect, and the sight of Maazel tearfully crumbling when a brief spark of joy reading to a child is unceremoniously cut short.

“We intend you to feel the problem, to experience it”, Maazel warned earlier on, and The Amusement Park makes good on that promise. Clearly, Romero—armed with a wad of church cash—did not come to fuck around.