Miyazaki’s latest The Boy and The Heron is fantastical food for your inner child

Octogenarian Studio Ghibli maestro Hayao Miyazaki evokes “the child in the adult and the adult in the child” with his newest fantasy, The Boy and The Heron. Luke Buckmaster praises it as a slow, strange, meditative journey.

Remember the tale of the boy who cried wolf? Hayao Miyazaki is the boy and his retirement is the wolf. The Japanese auteur has announced his career’s end several times, only to deliver another supposed swansong, followed by another, then another. Long may the fake-outs continue! The 82-year-old has had an indelible impact on cinema and is, in my opinion, the greatest animation director of all time—hardly a controversial take given his gobsmacking array of brilliantly beautiful and nuanced films, full of light and shade, bubbling with otherworldly effervescence.

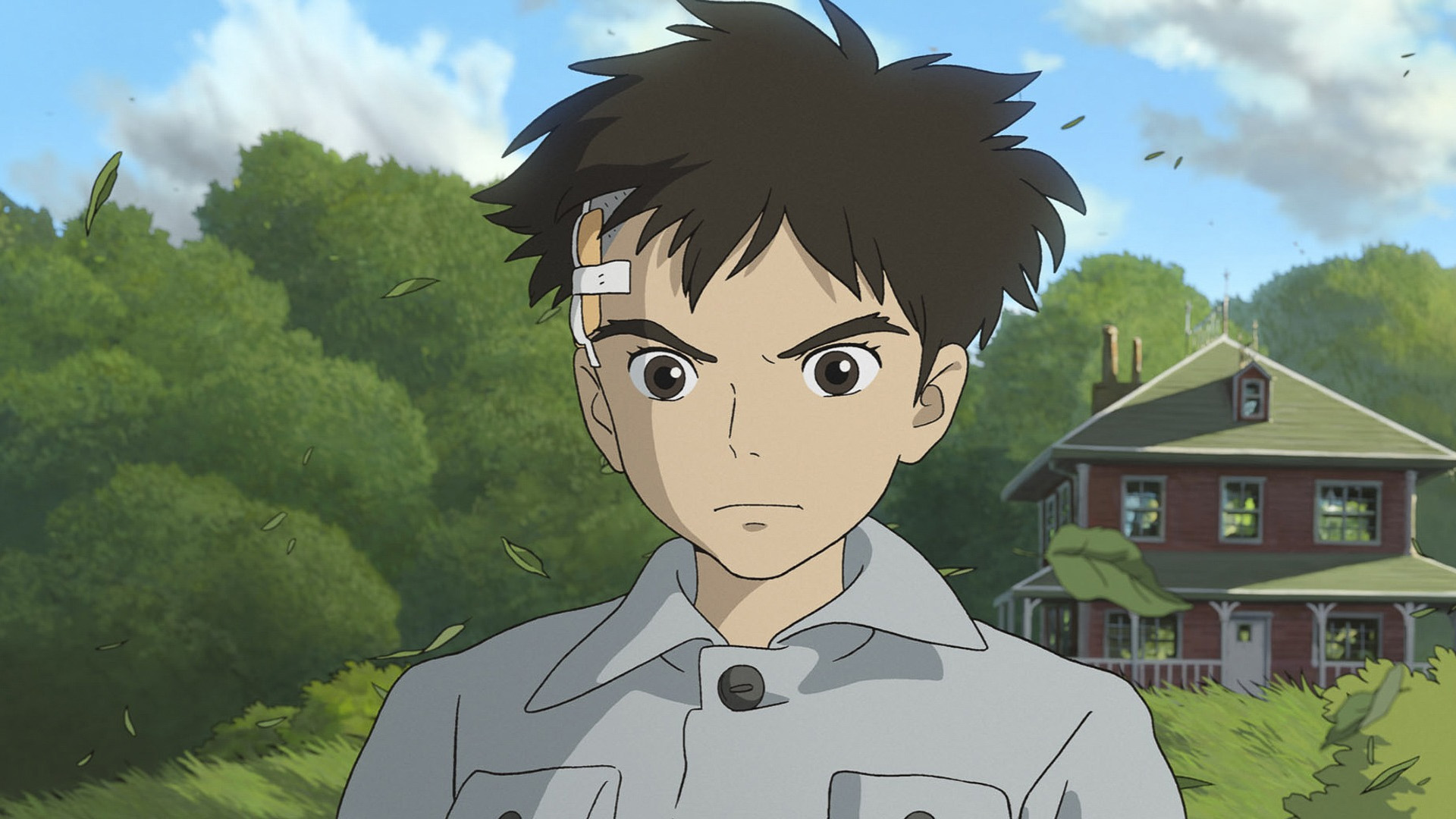

My personal Miyazaki favourites are Pom Poko, My Neighbor Totoro, and Spirited Away, though all his productions are wonderful in their own ways. Including his latest, The Boy and the Heron: a characteristically idiosyncratic story about a young boy named Mahito (voice of Soma Santoki in the Japanese version and Luca Padovan in the English dub) who moves to the countryside with his father following the death of his mother. It’s also to some extent about the titular heron, though audiences au fait with Studio Ghibli’s output won’t be surprised to learn that this is not an American-style talking animals movie. The bird does not deliver pop culture references or bastardise Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”.

I won’t explain exactly why the heron is a little…unusual. You can find that out for yourself. Suffice to say that the first time it calls out for Mahito it’s less a greeting than a blood-curdling shriek drawn from the depths of Hades—the stuff nightmares are made of. There’s pleasure to be had in figuring out the parameters of their relationship, one early clue arriving when the long-necked fiend (voiced by Masaki Suda in the Japanese version and Robert Pattinson in the dub) repeats the line “your presence is requested.”

This reminded me of the white rabbit from Alice in Wonderland, who fretted about the time: “I’m late for a very important date!” Both lines signify some kind of social obligation—a meeting or event from another world. Alice then tumbled down the rabbit hole, through one of the most famous magical thoroughfares, shifting her from one reality to the next.

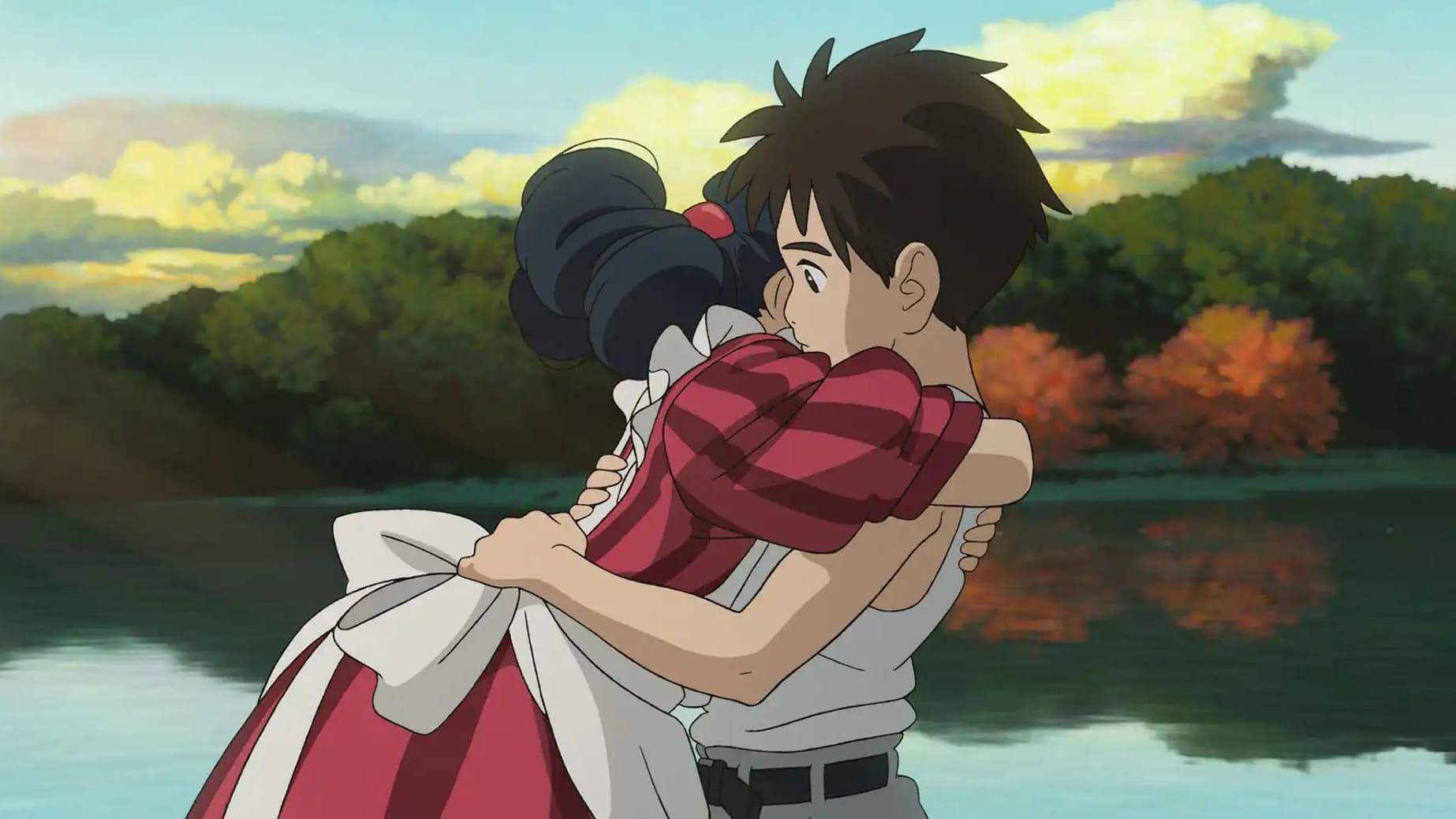

In The Boy and the Heron, Mahito similarly crosses a threshold into another universe, which, well into the runtime, opens the doors to the Miyazaki imaginarium. The old maestro serves up no shortage of trippy visions, from an army of giant parrots to puffy balloon-like things that embody the souls of humans yet to the born. His films are like David Lynch’s in that if you approach them as puzzles to figure out, their meaning will slip through your fingers like sand; better to take the red pill and contemplate large, imaginative, emotional truths.

By the time Mahito breaches the aforementioned threshold, you’ll be in the mood for things to get crazy—because the first act is long and unhurried. I suppose you could call it slow, but time works differently in a hand-drawn film like this; time feels tonal. You can always pause to soak in the beautiful unreality of it, which is true of all animations—and many live-action films—but it’s different here, partly due to the rarity (and subsequent novelty factor) of hand-drawn productions, and partly due to how Miyazaki juggles his elements.

Many environmental details are presented as unmoving globs of aesthetic, frozen in place. When we look at the trees, bushes, grass and shrubs surrounding Mahito’s home, for instance, they’re completely still, whereas in live action there’d be gentle movement: the rustling of leaves, the swaying of branches. When we do see this kind of movement—i.e. ripples in a pond during a dramatic moment involving Mahito and chanting frogs (naturally!)—it’s because Miyazaki is making this a focus point, and ratcheting up atmosphere. He has total control of the frame.

Wielding this control so discriminately, with the elegance and restraint of a master, achieves many things, including a rejection of contemporary animation’s worst tendencies: the idea the viewer needs to be infantilised by having every part of the frame, every corner and surface, pulse and vibrate and shake and shimmer and pop and crackle. That constant screaming of “look at me, look at me!” Miyazaki slows things down and makes things sparkle in different ways, evoking the child in the adult and the adult in the child.