Netflix’s tactful two-part Jimmy Savile expose A British Horror Story feels rushed

Netflix’s portrait of a serial abuser Jimmy Savile: A British Horror Story is certainly made for audiences outside the UK, Rory Doherty claims, in his review of this well-made yet frustrating docuseries.

There are two types of Netflix true crime documentaries; ones that contain substantial, legitimate investigative reporting, and exploitative ones that are more fascinated with a shocking, larger-than-life criminal story than sensitive filmmaking.

If it was pitched to you (and certainly if you heard the title), Jimmy Savile: A British Horror Story certainly sounds like the latter. So it’s a welcome surprise when Rowan Deacon’s nearly 3-hour limited series brings tact and an incisive lens to the story of one of the country’s most prolific and historic child abusers, even if the watch can be a frustrating one.

Aversion to watching this new doc among Brits may boil down to how saturated this story has become. It’s clear Deacon’s doc is aimed at a different audience than those who were old enough in Britain to remember the impact Savile had in entertainment culture, or when waves of victims stepped forward after his death. Younger, uninitiated people and overseas viewers are who the series is being pitched at (making Netflix’s platform the perfect place for it), something illustrated by the amount of time it takes to build an impression of how pivotal and beloved a position the working class, Northern DJ and presenter held in British pop culture.

Through a wealth of archival footage, we get to see decades of people bowled over by his charm and eccentric personality—and Deacon makes sure to include every instance of his buoyant inappropriateness that now comes across as huge red flags of his creepy nature. Touches of manipulative music let you know when you’re to feel unpleasant towards his behaviour, a choice that would feel less necessary if we didn’t wait over two hours to hear directly from any of Savile’s victims.

To Deacon’s credit, the testimony we do hear is gut-wrenchingly powerful, and words can’t express how horribly affecting it is. What does feature early and plentifully, by contrast, are identifications of individuals or institutions who knew or outright permitted Savile to have power over vulnerable children, something that was allowed throughout his whole career.

This is where the talking heads shine; incredible research has gone into interviewing a wide range of people who crossed paths with Savile. Some are confronted with uncomfortable reflections that they could have enabled his abuse. While it’s commendable Deacon lets these flawed perspectives speak for themselves without instructing the audience how to feel, it’s frustrating when people keep attesting there was a “good”, charitable, altruistic side to Savile, and a “bad”, abusive side. It’s startlingly obvious to anyone that everything philanthropic he did was all to give him access to victims, and to protect him from suspicion or criticism.

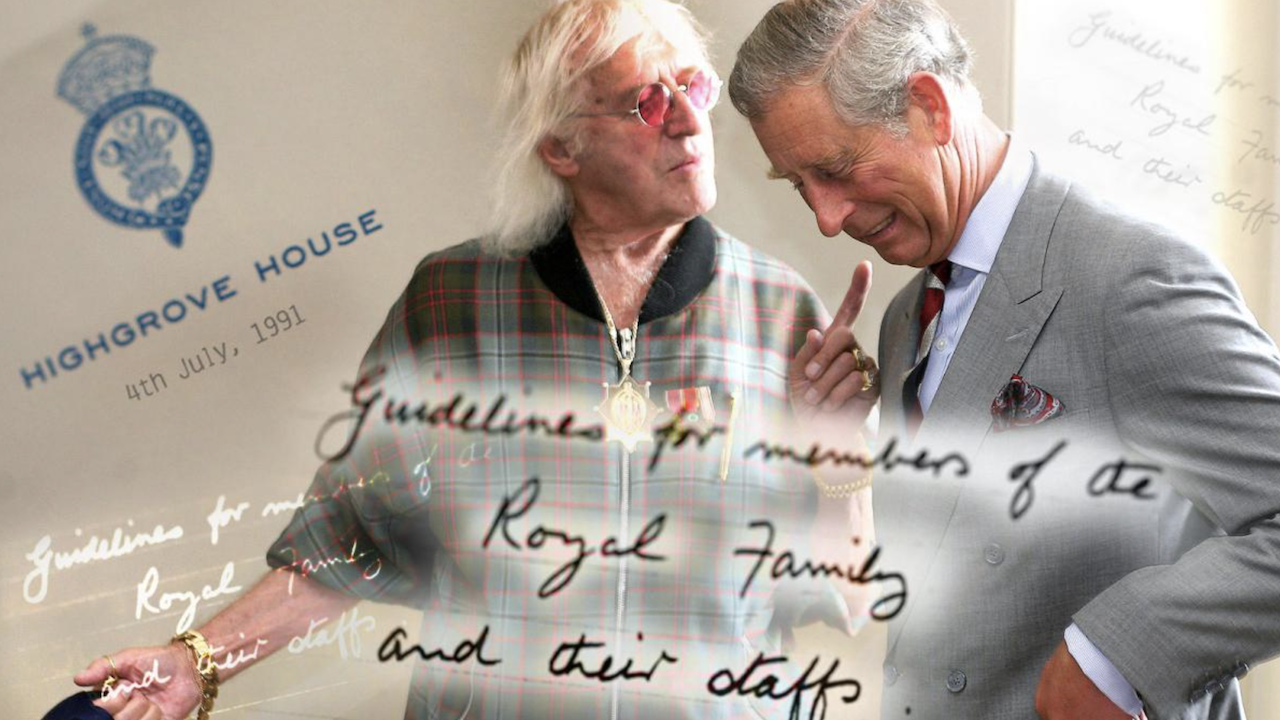

Each revelation that someone willingly and wittingly left him alone with minors is staggering, as is the ignorance protested by everyone at the several hospitals he carried out most of his abuse at. It’s illuminating, detailing the extent of the close friendships Savile held with Margaret Thatcher and high-ranking members of the Royal Family thanks to close aides and recovered letters. While the reasons he was so appealing to the Prime Minister are explained, Deacon largely uses these relationships to surprise rather than unpacking why someone like Savile was protected.

Context is key to understanding why Savile’s crimes were so extensive, and why it was impossible to levy accusations at him until after his passing (despite the BBC still protecting him and suppressing investigations). Deacon effectively details how Savile’s fame was chipped away by a rising tide of rumours, as his relevance as a presenter faded in the 90s, anti-paedophile crackdowns in the police force increased, and the internet offered a space for victims to share glimpses of their experiences.

This is all welcome material, but for some reason the same depth of approach is not brought to the breakout of accusations post Savile’s death. The closing segment where people discuss the coverups ends up feeling a little rushed, with Deacon’s piercing documentarian eye not revealing as much of the institutional protection as it did before. Maybe that’s a whole other documentary that needs to be made. If it does, Deacon has shown herself to be more than capable of handling such a task.