Vital NZ film communicates trans experiences like no other

Aotearoa drama Rūrangi returns from the New Zealand International Film Festival for a nationwide cinema run. Film critic Amelia Berry breaks down why the movie’s clarity, lightness, accessibility, truth, and joy make it a triumph.

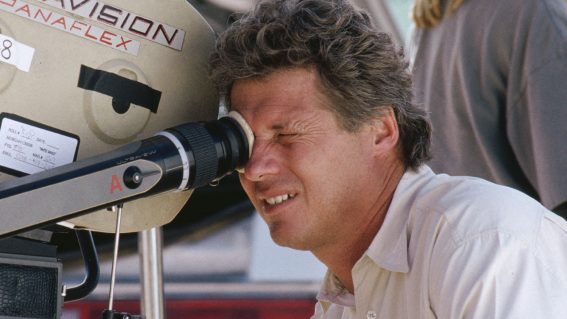

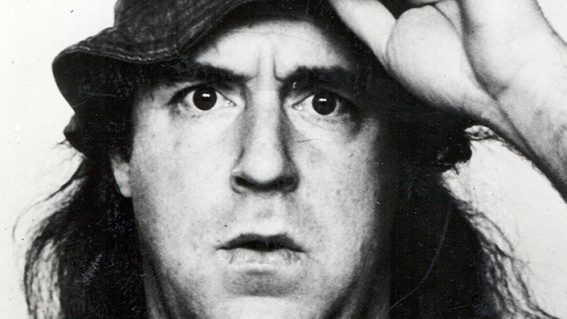

“Who benefits from our shame?” This is the central question of Rūrangi, the new film directed by Shortland Street veteran Max Currie, and written by queer educator and activist Cole Meyers. Every morning Anahera (Āwhina Rose Henare Ashby) wakes up reciting her pepeha. She wants to reconnect with te reo Māori but can’t bring herself to reach out for help. Caz (a stunning debut performance from Elz Carrad) returns to his hometown for the first time in a decade, for the first time as an out trans man, and struggles to rebuild his relationships with his father, his best friend, and his ex-boyfriend. He’s ashamed of being away for so long, of the hurt he’s caused them, and of the things he’s missed. Alongside these, there hangs the familiar spectre of suicide, a nexus of personal, political, and national shame.

See also:

* All movies now playing

* All new streaming movies & series

* The best movies of 2020

If you know anything about Rūrangi, you know that this is a ‘trans film’. The lead, the writer, and much of the cast and crew are trans, and the story is in a very essential way trans. While transgender visibility is at an all-time high, in general terms transgender representation hasn’t moved all that far ahead of “Glen or Glenda”. So, even with its shining gender diverse credentials, it’s frankly shocking that Rūrangi has managed to make a film about transgender experiences that has this much clarity, lightness, accessibility, truth, and joy. Even the darkest moments of this film feel like a triumph because of the deftness and fresh approach with which they’re handled. For a trans audience, seeing Rūrangi will feel like coming home for the first time.

This is not to say that Rūrangi is a perfect film. Having started life as web series, re-cut for cinematic release, some moments (particularly the sweet, if slightly eggy final moment) feel like they’re better suited for the small screen. The shorter run-time also means having to sacrifice some of the lighter, more fun moments in the story’s second half in order to fit in all the plot. Criticisms like this can’t help but feel petty though, in the face of a film that’s so often brilliantly shot, with unmistakably incredible central performances from Elz Carrad, Kirk Torrance, Āwhina Rose Henare Ashby, and Arlo Green, a film that tells a vital, essential story about being trans, and about being Māori, in Aotearoa today.

Who benefits from our shame? We might be tempted towards a prosaic answer: nobody. But Rūrangi isn’t afraid to show us how our shame is leveraged and weaponized by the powerful, the spiteful, and the comfortable. It shows us too, how to move beyond our shame. When Caz first returns to Rūrangi and sees his father for the first time, he gives him a potted explainer of what it means to be trans. His father is unmoved. Rūrangi understands that shame, bigotry, pain, aren’t rooted in a lack of information, aren’t remedied by explanations or excuses—we grow beyond our shame through community, through shared experiences, and through communication and understanding. A strikingly apt message for a film which communicates trans experiences like no other before it.