Pam & Tommy is an addictively entertaining history lesson – full of sex, drugs and wobbly bits

Everyone expected a salacious romp, but the wildly entertaining Pam & Tommy delivers much more. It’s an underdog story, a gangster drama, and even a history lesson about the internet, writes Luke Buckmaster.

Creating a sense of nostalgia is about evoking a particular feeling, of a particular time and place, in relation to a particular sex tape. Alright: that last bit is a genre-in-progress, nudged forward in its evolution by creator Robert Siegel’s very engaging eight-part series Pam & Tommy, which is a fine example of how to pry open a single event, or issue, from numerous narrative vantage points. Some perspectives are obvious, several are unexpected, and all are connected to the theft and distribution of an infamous home video made in the mid-90s.

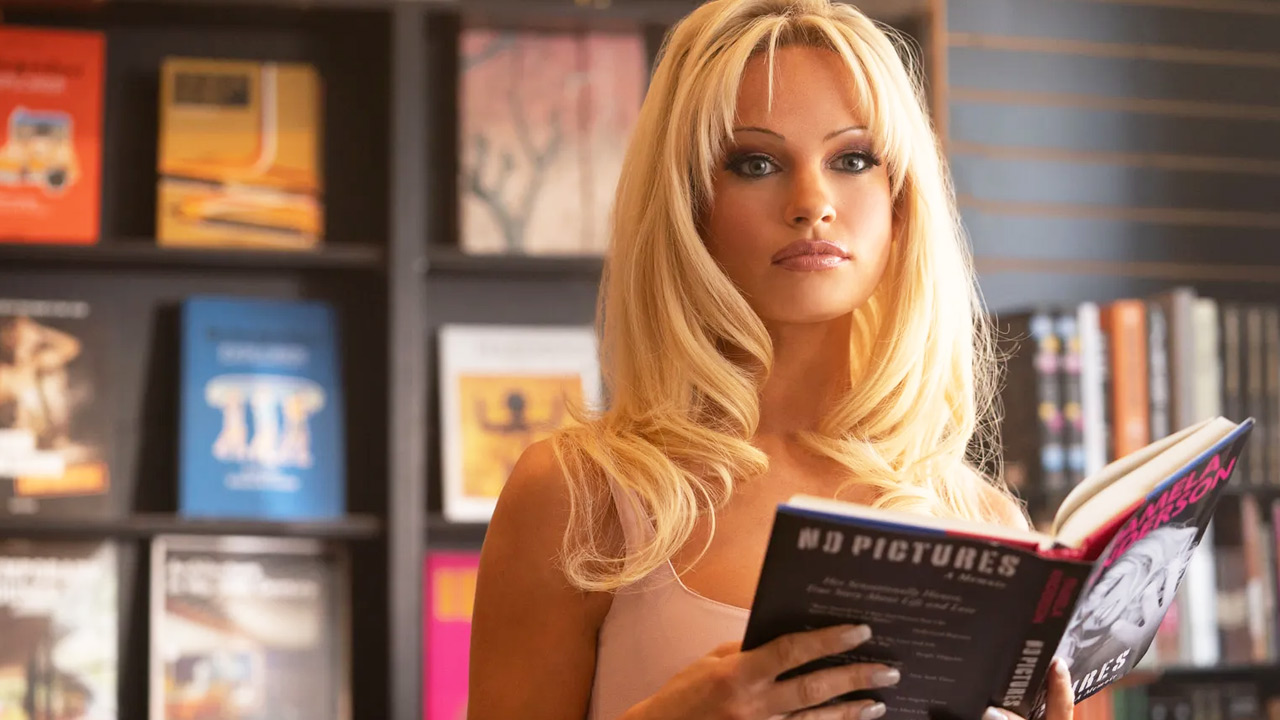

This video was of course filmed by and starring—at various points of undress and, um, enthusiasm—super-celebrities Pamela Anderson (Lily James) and Tommy Lee (Sebastian Stan). The show’s cheeky humor is evident before it even begins, in the double entendre title of the first episode—which is called “Drilling and Pounding.” The non-indecent meaning refers to building and carpentry, and possibly also what’s going on inside the mind of electrician Rand Gauthier (Seth Rogen), whose work involves dealing with—in the words of a colleague, like him, tortured by clientele with horrendously unreasonable demands—“fuckin’ rock stars.”

One in particular: Lee, who insists on all sorts of changes to the reno plans for his Malibu mansion, already very sweet digs, including the sort of architectural alterations you don’t see on The Block—i.e. shifting his bed a few feet to get a 360 view of the shower. Guathier is assured by (the often drunk, often gun-wielding, often underwear-clad) Lee that “money is no object”—a phrase that’s all well and good, and very impressive and all that, so long as the utterer coughs up the dosh. Which Lee doesn’t.

Gauthier’s troubles intensify when the Mötley Crüe drummer not only fires and refuses to pay him, but won’t even give him back his toolbox, telling him to “get the fuck off my property” while waving a shotgun in his face. The man is a total prick, in other words: the kind of self-absorbed “bad boy” who commanded the stage back in the 90s, in a way these men don’t and cannot in the present cultural moment, their cachet and the public’s overall appetite for wildness having eroded in the post #MeToo era.

Screenwriter Robert D. Siegel is on Gauthier’s side, framing the intro episode as a moral justification for the upcoming theft—of the loot rather than the video. The latter has different ethical implications, ultimately revealing uncomfortable truths about sexism in society—for instance the way members of the public shame Anderson but celebrate Lee.

Siegel also downsizes Gauthier’s career (or side career) as an adult porn star, which is detailed in the entertaining longform Rolling Stone article on which the script is based. This was probably to make his character more relatable, a task helped in no small measure by Seth Rogen—a deceptively good actor and a very appealing “everyman,” providing an anchor to guide viewers through a narrative world populated by the rich, the famous, the hedonistic, the well endowed.

The title and premise of the show, coupled with its unexpected focus on Rogan’s character, is almost a bait-and-switch: you think it’s going to be about Pam and Tommy but it’s actually about the guy who ripped them off—at least initially. In the second episode attention moves to the titular lovers, establishing a tendency for unpredictable perspective-shifting that keeps the show fizzing along nicely over its eight episode arc. The first three were directed by Australian filmmaker Craig Gillespie, whose work includes I, Tonya—a sharp and bitterly funny biopic that raises interesting questions about guilt and implication.

In Pam & Tommy the titular characters are captivating not because they’re likable, but because they’re embodied fantasies: of wealth, excess, erotica, fame and fortune, rock’n’roll. There’s a shallowness about them, an emptiness, a sense of stunted growth that makes these people almost pitiable despite their cashed-up, bizarro fairy-tale lifestyles. Chatting on a plane after their wedding, the pair sound like adolescents, discussing her favourite food (“french fries!”) and his favourite movies (“horror’s my jam!”).

The tone of the series is knowingly playful and occasionally outlandish. In the context of the latter, one scene stands out: Lee, high on ecstasy, has a conversation with his penis about how Pam may be “the one”, his wildly animated anatomy moving, bending, and talking back to him, brought to life by four puppeteers operating an animatronic penis. Once watched, never forgotten, a yada yada. Even with the energetic, trash-talkin’ erection, these people are exhaustively vacuous, making the show’s jumps in perspective and dovetails away from their lives welcome.

As a cultural artifact the sex tape is what it is, unlikely to be discussed alongside Fellini and Griffiths in cinema studies class any time soon. But the distribution of the tape is another, more historically and in this instance more dramatically interesting matter, occurring during the early days of the internet—well before the age of high speed video streaming. The challenge of how to disseminate what was, in effect, an item of contraband provides another compelling tangent, with Gauthier collaborating with porn impresario Uncle Miltie (Nick Offerman) and later, more ominously, with a loan shark and organized crime.

The show’s unexpected veer into gangster movie territory brings us back to Pam & Tommy’s greatest asset: its ability to take that single event or issue and fill it out laterally, and in narratively interesting ways, crisscrossing genres. This is wealth porn; this is an underdog story; this is an action-heist; this is a crime drama. This is a history lesson about the internet—though not, as they say, the kind they teach in schools.