Trent Reznor opens up about Hurt in a new episode of Song Exploder

A new season of Netflix music documentary series Song Exploder lets Tony Stamp soak up insights about one of his favourite albums, Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral.

At some point in my teenage years, I became aware of a show called VH1 Classic Albums. I’d been turned onto music when I was fourteen and someone showed me how to play ‘Smoke On The Water’ on bass guitar; more specifically the one rickety bass in Papatoetoe High’s music dept (alongside a few equally rickety acoustics). From there I started playing in bands, and at some point entered an actual recording studio, which triggered a lifelong love affair with those hallowed spaces. I studied music production for a few years at MAINZ, and never looked back.

Classic Albums was like a gift from above, as the programme-makers went into the studios where albums by artists like Fleetwood Mac, Nirvana, and Lou Reed were made, and pulled up the individual elements of their hit songs. When I learned that the ocean sounds on Electric Ladyland were made by Jimi Hendrix blowing into a mic it was like the secrets of the universe were opening up to me.

See also:

* The 20 best shows of 2020

* The 20 best movies of 2020

* All new streaming movies & series

I’m not sure if Hrishikesh Hirway was a fan of Classic Albums, but I suspect so. He started the podcast Song Exploder in 2014, building it around a similar premise: musicians are interviewed about one of their songs, and as they talk we hear each individual element in isolation. How a certain drum sound was achieved here; why a certain vocal was sung there. It demystifies the process of music-making in the best possible way, and this approach can access truths that may otherwise stay hidden. Musicians generally like talking about their craft, and that can open them up to other things.

An appearance on the podcast is increasingly sought-after. The three most-recent episodes feature Common, Jewel, and Billie Eilish—not exactly small names. And this popularity has led to an expansion in the form of a series on Netflix. Featuring artists like R.E.M., Dua Lipa, Alicia Keys, and others being interviewed on camera by Hirway, it covers slightly broader ground than the podcast in terms of each artist’s life and career, before the host pulls out a laptop and gets stuck into the bones of each track. The artist listens and casts their mind back to where they were when it was made.

Around the same time I was discovering Classic Albums, I discovered Nine Inch Nails. A Canadian exchange student friend brought over a double-cassette version of their 1994 album The Downward Spiral, and after one listen I was hooked. An intensely confrontational album, it synched perfectly with a certain type of hormonal angst, but more importantly for someone learning about production, featured techniques that were mystifying and fascinating, and to this day sound cutting-edge.

Essentially a one-man act, Nine Inch Nails albums are the result of lots of studio boffinry by Trent Reznor, a man whose career got started when he studied classical piano and computer science. Put those two skills together and you have a road map for what became known as industrial music. The Downward Spiral was NIN’s second full-length, a ludicrously ambitious concept record about self-harm that ticked off an element of its protagonist’s life with each track. It’s still one of my favourite albums.

So I was very happy to see Reznor sit down with Hirway for an episode focusing on TDS’s final track Hurt. For a musician whose career was defined by youthful anger, writers’ block and long waits between albums, it’s been fascinating seeing him mellow into such an amiable fellow, increasingly prolific thanks to his soundtrack work with Atticus Ross (I never thought I’d hear the man responsible for the Closer refrain “I wanna fuck you like an animal” contributing to a kid’s film, but here’s the soundtrack to Soul!)

Watching him listen to his isolated vocals on Hurt and reflecting on the man who sung them is eye-opening, even for someone like me who’s read a lot of his interviews. He first notes how out of tune he was, then remembers how long he spent trying to sound quiet and strained. After bellowing every other lyric this evidently took some work. It was maybe the first time he’d sounded truly vulnerable on record.

Hurt was the song David Fincher and his crew listened to every day on the set of Fight Club, for obvious reasons (the opening line is ‘I hurt myself today/ to see if I still feel). It’s the album’s protagonist reflecting on all the violence and debauchery we’ve just heard (which culminates in their apparent suicide). Twenty-six years later, a bearded, bespectacled Reznor (now 55), reflects to Hirway “When I wrote it I felt alone. Lost. But things will be ok, you know? You’re ok.” His voice cracks slightly.

Hirway provides narration for the episode, but as an interviewer he’s admirably quiet (in the podcast he’s almost entirely absent, so the brief moments we see him work here are illuminating). The show’s focus always stays on the musician, and even more so, the music. It’s by focusing on the song that we get to the subject’s inner lives.

To be fair, Reznor’s never been shy about his various anguishes, but he resists talking about lyrics, despite Hirway’s gentle insistence. He says songs are ruined when they’re demystified too much and laughs when he asks Hirway “What are you tricking me into doing?”

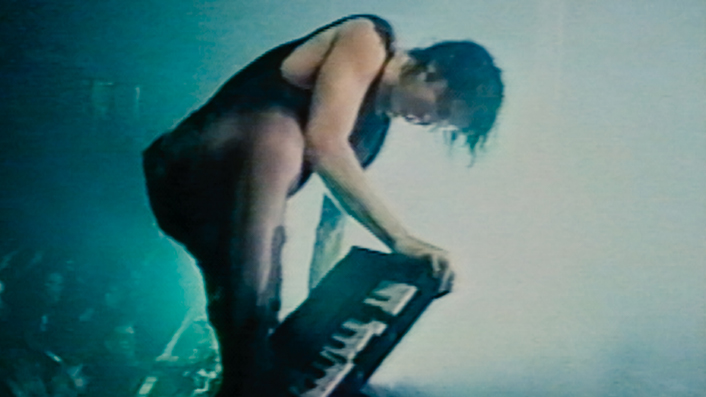

When you’re a musician of this stature you get pretty media-savvy. But he’s happy to talk about his mental state at the time of writing. “I was trying to find purpose and salvation and a sense of place, and just to not feel bad”, he says as we see archival footage of him smashing things on stage, drinking, and partying with Pantera.

After lyrics, it’s onto sound design. Hirway pulls up the drone that opens the track, and something I’d wondered about for years is answered. The sound is from a device used to ‘tune’ a studio (make sure the frequency range is well represented). Reznor sampled the sounds it generated, and claims to still use them “all the time”. When a particularly windy clip from David Lynch’s Eraserhead plays, another penny drops. Reznor says he was trying to replicate Lynch’s trademark unease, but qualifies “It’s not just about repulsing you. I was setting the stage for what I wanted to get across emotionally.”

The song is further pulled apart: layers of guitars and sampled strings. Legendary British producers Alan Moulder and Flood pop up to talk about Reznor’s approach in the studio, but only briefly. It’s worth emphasising how impressive it is that Hirway gets this much access—not just to the artists and peripheral figures, or old footage, but the multitrack tapes. It’s what the show is built on, and it can’t be easy to get signed off. Watching musicians have each tiny element of their song exposed does feel really personal, like they’re airing their secrets. With Reznor, you can see him reckoning with his past self as he listens. It wasn’t always a given that he would age as gracefully as he has.

It’s also a chance to see him talk about Johnny Cash’s version of Hurt, the most well-known version of the song. I assume most people don’t even know it’s a cover. I’d sometimes wondered how Reznor felt about his song being eclipsed by a legendary performer’s version of it, and it turns out he’s grateful. “At the time I was unsure about my ability to write, and my relevance, and I felt adrift. That song reared up again to kind of let me know things will be ok. It felt like a friend almost, like a hug”.

For anyone interested in music production, Song Exploder is a godsend. Music shows, in general, are thin on the ground, let alone ones that pay such attention to detail, or get such enlightening responses from their guests. The variety of musicians profiled is also to be applauded, and it’s a sign of where the music industry is that this feels like very niche programming. So let’s hope it continues, and maybe even inspires similar shows to be made. I can only imagine what the average Dua Lipa fan will think after watching her episode and letting Netflix autoplay, learning of the tortured young man who made an album about self-destruction that went on to become a hit.