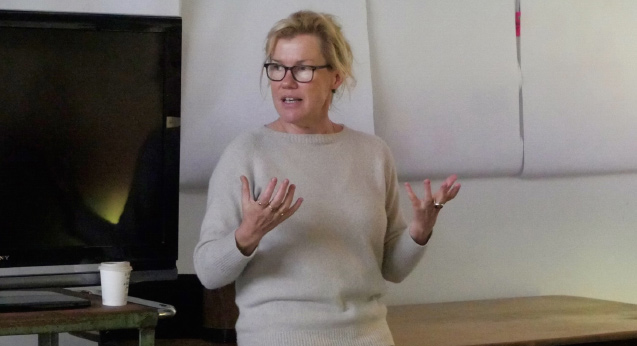

Robyn Malcolm on acting, female characters and industry sexism

Throughout her career, Robyn Malcolm has worked nationally and abroad, playing some of stage and screen’s most compelling women. Now, she says, she’s particularly interested in exploring characters who are afforded the same breadth of fallibility as their male counterparts.

As Flicks celebrates 40 years of New Zealand film, Amanda Jane Robinson caught up with Malcolm to talk about complex female characters, industry sexism – and training a new puppy.

ROBYN MALCOLM: If you hear a high pitched barking and scolding from me it’s because I’ve got a new puppy and she’s behaving very badly this morning. Her name is Tara and she’s a border collie retriever cross. I’ve never had a dog before, she’s an absolutely awesome little creature who does exactly what she wants when she wants. She’s super cute. Hold on a minute, she’s just gone out, I left the door open and she’s going out to attack a cat. What are you doing? Oh, now she’s got my underpants. You can’t be in here! Sorry Amanda, I’ll be two seconds. Come here, you ratbag.

I’m shooting just outside of Adelaide doing the third season of Rebecca Gibney’s show Wanted, which is actually fabulous. Rebecca; she’s a force that woman; she’s made this show which is like Thelma & Louise on Aussie TV about these two women who meet at the beginning of season one and are basically just on the run. What I love about it, too, is that there’s a huge percentage of female characters right across the board and the stories are female-centric without involving love affairs and romances with men. It’s great. So I’ve been in all these little towns in Australia, driving in the outback, it’s been absolutely brilliant. Then coming back here and trying to be a mother to my two boys and a mental dog. It’s a little bit crazy.

FLICKS: I know you wanted to talk about the dearth of great roles for leading women. Is this a recent frustration or something you’ve experienced your whole career?

It’s tricky really because a lot of the work that I’ve done here has been in television. Getting to play a character like Cheryl West for six seasons was brilliant because she broke a lot of rules in terms of female behaviour on screen. And then the kind of film work I’ve done, I’ve always been a character actress. Then there’s a much broader range of female leads in theatre. I think down here in New Zealand and Australia we’re a lot more conscious about some kind of storytelling equity. I’ve just spent four and a half months in the States and I don’t think we’re anywhere as bad as there, or the UK or even Europe for that matter, those big places that dominate the storytelling industry.

I feel that there’s a more entrenched sexism in Australia. Again, it’s not as bad as the States, but you do feel it; it’s much more influenced by Hollywood. But then I also notice that there are a lot more women in positions of power in Australia; more producers, directors, DoPs; than there are here, though I believe that’s changing. I think it’s really interesting that in Hollywood before 1925 fifty percent of screenwriters were women, before it was established that filmmaking could be a serious money-making venture. When it was still regarded as a bit of a folly, women were allowed in the front door, so you have some extraordinary women who were writing and directing some amazing films, silent films and early talkies, and they weren’t rom-coms, there was a huge range. I remember reading a quote somewhere that Hollywood was built on the hard work of outcasts; women, immigrants, and Jews. And then the money men turned up and that all changed.

One of the things I’m really interested in right now, and of course I would be, because of my age, is I find it really interesting that female characters in film have to fit within a much more rigid framework than male characters in terms of their behaviour, not only what they look like. Women aren’t allowed to behave as badly as men. And there are always exceptions to that rule, but most of the time they have to sit very comfortably within certain archetypes; you’re either the whore or the madonna, if you’re angry then you’re a psycho unless it’s an appropriate kind of anger. And I think all of that, over the decades, has directly fed into an all-pervading sexism right through society. Then on top of that, there is an ageism, so you’ve got to be young and if you’re not then you’ve got to look young. You can’t look like a normal older woman because that’s just not apparently what people want to see, which is utter bollocks. So for me, what I’m interested in at the moment is older, badly behaved female characters. Or more fallible.

I think that’s also the problem is that now we need to be careful we don’t get too serious about ourselves either, because then we lock ourselves into some kind of behavioural prison in the other direction. Because no one’s perfect. This is all we talk about now, the meaning of patriarchy in film and television and what does it mean to break away from that. So few stories about us have been told, there’s such a massive range of stories out there that haven’t been approached.

I remember Gena Rowlands said “There are vast areas of the female experience that haven’t begun to be tapped.” And that was what, fifty years ago.

Oh god yeah, and told by women and women who are feeling confident enough in this industry to know that they can tell stories without rules, that there isn’t some male-dominated commercial imperative that they have to adhere to. I’ve got two nieces and one has just turned ten and the other one is about to turn seven. I recommended The Princess Bride to their mum to watch as a family. This ten-year-old sat down with her mum and two-thirds of the way into the film said “So when’s Princess Buttercup going to do something?” And her mum went “What do you mean?” And she said “Well she’s just sitting around, when is she going to have a swordfight?” And my sister had to say “No, she’s not.” What’s interesting is that the ten-year-old just went “Why?” Like, she had an expectation. She found it a curiosity. Then I took my younger niece when she was five to see Cinderella and this wee five-year-old said to me “How come it’s the prince that gets to make the choice?” and I’m just delighted with those two. It’s not something their parents have drilled into them, there’s no ranting and railing going on in those homes, but their world is different already.

Their expectations are already different. I just think that’s phenomenal. We all grew up on those fairy stories and we didn’t question them. We’re having to recalibrate everything, and it’s really vital that we do.

The other side of it as well, which I think is probably where it begins and ends, is money. Follow the money. Men have been paid more than women in this industry forever, and I’ve experienced that. To me, that’s probably the most important bit before everything else, that when there’s a pay inequity between female and male directors, actresses and actors or whatever, that’s sending is sending an incredibly powerful message that one gender is more important than the other, and everything else trickles down from that.

Is the other actors’ pay something you always know up front? Do you ask?

No, you don’t know. Sometimes you ask. I know of stories where the woman will go “I want what he’s getting” and she won’t know but she’ll ask for that. Or, now, what’s interesting is male actors will go “I won’t do it unless she’s on the same pay scale as me.” Sometimes it’s the agent or the representation that failed because they get scared of pushing it. There are some amazing men now who are working for what we’re working for and absolutely believe in it and get that the more breadth of experience and behaviour there is for female characters, the more interesting it’s going to make the male characters.

That’s such a great tangible action with regard to pay.

Absolutely! They can take care of it.

Have you found that working with a female director changes a set in terms of the power dynamics?

I’ve been really fortunate. I’ve worked with Jane Campion who is all about that and makes no apology for it. She doesn’t even feel the need to have a conversation about it, she just tells the stories she want to tell. And I’m working with Jocelyn Moorhouse now and she’s all about that. It depends on the personality of the director. I suspect that there are women directors who are so nervous or so keen to hold onto certain positions that they play the game more than others, and that can be understood as well.

I’ve heard actresses argue that women are their own worst enemy and women attack other women. And I understand it, like, we’ve been sitting around the big feast of entertainment that the men have all had the big chairs at and they’ve thrown us the odd cupcake or saveloy and we’ve had to fight. We’re fifty percent of the population and we’ve had to fight for twelve percent of the work, and so it gets competitive. But that’s simply a response to the reality of it, which is that we all want to work. Sometimes that competitiveness can get a bit rough in terms of how women get with each other. But that to me is just symptomatic of where we’re at, it’s not that women naturally want to undercut other women.

In terms of my experience, I’ve worked with some fabulous women. And I’ve worked with some really sexist men and some really wonderful men, mostly, and it’s always a great experience. With women, you just know there’s a slightly different eye. I think it’s interesting that the predators, the assholes in the industry, they do prey on the weak. They’ll find someone who’s insecure or nervous or frightened or feeling powerless and they’ll go for them. Sometimes I will them to me, I see them every now and then and I think “Come on, just do something, say something, cause I just really want to rip your balls off,” and they don’t, because they know. I know more women like that, more women in the industry in New Zealand and Australia like that, who are just like, “Don’t even bother trying,” which is really healthy and how it should be

The other side of it as well is that actors, on the whole, have very little inhibition when they work, because that’s part of our jobs. We have to be open with each other and the people we work with. You’ll hear the dirtiest jokes on a film set, and I’ve told them. I don’t want that to go, because that’s part of the way actors are, we have to be loose. But when that gets messed with and pushed into another territory, that’s when it gets toxic. And a lot of that is to do with women drawing the lines of what’s okay and what’s not okay, women taking responsibility for that, women saying “Hey that’s not cool,” but knowing when they say that they’ll be backed up. I’ve got lots of stories of young actresses who have spoken to me when they’ve been treated appallingly and they’ve either gone to management and not been supported, or they’ve not gone to management because they know they’re not going to get any backup, and that’s really hard.

Has the Me Too movement resonated with your experience? You said we’re not as bad as the States and Australia with sexist roles, but have you found that you’ve experienced that with men behind the scenes?

Yeah, I reckon, definitely. Financially I’ve experienced it. And early on I experienced first-hand stuff, like “Oh let’s hire her, she’s got lovely big tits”, I remember hearing that when I was very young. I’d just got out of drama school and I was up for a commercial and this director said it right in front of me. And I didn’t know what to do then.

I had an experience way back when I was doing a play and in the play the character was raped under a sheet. And the actor, at the point of the ‘rape’ I guess, used to punch me in the crotch. And it took me a while. For a minute there, because that’s how actors are, I thought, “Oh, is that what you do? Is that part of it?” And I went with it. Then I got really uncomfortable after about a week and I spoke to another actress about it and she said it was absolutely wrong. So I went to the actor and I did what young women do, I was 21 I think, and I said “Thank you very much, I know you’re trying to help with the impact of the moment, but I can act it, thanks.” And he apologised and said “Oh of course, of course, of course, I’m so sorry” and it didn’t happen again, but had I not said anything it would have gone on and I would have just felt worse and worse. I was terrified of confrontation back then so I made it okay, which is what women do.

I’ve had lots of male comments on my physique or what I look like and every now and then I’ll bristle and I’ll tell them to shut the fuck up, or I’ll ignore it. I haven’t been on the end of it but I’ve seen awful, awful behaviour. I’ve seen women completely crushed by it and I’ve seen other women deal with it. A lot of that is to do with their position in the industry, whether they feel like they’ve got any power at all to fight back or whether they feel utterly powerless, whether they feel like they’ve got some backing or support and I feel like that’s the same in any industry, it’s all about where your support network is. I’ve just seen some horrific behaviour, horrific. And that’s the other side of it; there are often lots of people around and they all allow it. I think that’s the whole problem around Weinstein, is that if the person is powerful enough, people know and don’t say anything.

It’s a really fascinating time for us as women. I think it’s important we stay really fucking furious, really fucking stroppy, and also have an excellent sense of humour right the way through, and have an excellent and courageous sense of ourselves as women in life and our stories. The one thing we don’t want to do is get self-righteous and overly serious. We’re talking about art. We’re talking about the honest reflections, an analysis of the human experience, and that’s not a moral issue. That’s about who we are as humans. That means the lines can get really blurred, so we’ve got to really be careful of that too. It’s deeply complex and completely wonderful. Anger and laughter are the two gateways, I think.

Have those complex, artful roles that you’d have loved to play been within New Zealand film, or have you had to look elsewhere?

I have to think globally because I don’t think there are that many here. I mean, Beth Heke from Once Were Warriors is an incredible character. I’ve seen a lot with young short filmmakers. It’s interesting, isn’t it, I can’t think of that many from New Zealand, not in the mainstream. Morgana and Rima’s characters in Housebound were great and broke a lot of rules about female behaviour on screen.

Of late, one role I’ve adored is Olive Kitteridge from Frances McDormand’s four-part television series. One of the things you hear a lot from producers and networks and distributors, and I’ve heard this directly, is that “She’s not very likeable.” But that’s got nothing to do with it, that’s not the human experience. People don’t want to watch likeable people all the time, people want to watch human people, people they respond to. Olive Kitteridge did a whole lot of stuff you’re not allowed to do; she wore no makeup, she was in a bad mood, she was menopausal, getting into old age, she didn’t have sex, she didn’t wear sexy stuff, and she didn’t say nice things to people. And she was utterly compelling, heartbreaking, interesting, and incredible.

There was a film I saw a while ago called Gloria about an older single woman who has an affair with an older man, and I adored that. Again, watching a woman in that middle stage of her life is so much more interesting and complex than watching a 22-year-old fall in love for the first time. There’s just so much life experience going on there. Then on the other hand, what I found so fascinating was the two female characters in Blue Is the Warmest Colour. I loved that and then what was so interesting to me was the moment they had sex the film went tits-up for me, because suddenly I felt like I was watching a couple of porn actresses and not two characters. That male director could not get his gaze out of the lens, only in that scene. They’d built up these two brilliantly complex young women who’d fallen in love with each other, and now I can’t see them. Annette Bening’s role in 20th Century Women is one recently that I just loved. I love what she does, she makes some great choices that actress. In New Zealand, it’s interesting, isn’t it? There haven’t been a lot. Christine Jeffs’ Rain.

That’s one of my favourite New Zealand films!

It’s great, isn’t it? Sarah Peirse’s role in that is just phenomenal. There’s a few, not a lot though. I’m hoping as our screenwriting becomes more and more complex and more and more interesting as the decades go on, that will go hand in hand with how we approach our female characters. Of course, Holly [Hunter]’s role in The Piano was extraordinary. And Crush is another one. And Jane [Campion]’s first film Sweetie.

That reminds me, I’m studying now and last year I took three film theory classes and only one of them had any films made by women on the syllabus.

That’s shocking. Gaylene [Preston]’s a singular voice here and has been for a long time. But it takes a long time to get a film up, and when there’s only two or three actually getting the money to make films…I mean, that really needs to change though. I was having that same experience and I was on a plane trying to find a film directed by a woman or if not, one with a strong female character. And I saw The Philadelphia Story with Katherine Hepburn and Jimmy Stewart and Cary Grant, and she’s the central character.

I thought “Oh good, I’ll watch that”. And she’s glorious, you know, she’s Kate Hepburn, and she’s stroppy and has her square shoulder pads and she’s a working woman and then, I’d forgotten this, but by the end of the film she’s in tears apologising to her father who left her mother and saying it’s all her fault, and he’s saying it’s all her fault because she was a badly behaved daughter and that’s why he left home, and that’s why he slept around, because she was too stroppy! And I was sitting on the plane going “What? What?!” Far out. Even Kate Hepburn, for god’s sake. I remember doing film courses at university and I probably went through a whole course watching films directed by men and I wouldn’t have even noticed. The fact that you even notice is kind of a really big step.

Yeah, I guess that’s true. I’m interested in what you were saying before, that directing was seen as a woman’s domain when it was seen as a folly, and I find that similar to how costume or makeup or production design are seen now.

Yeah, if it’s wardrobe and makeup that’s okay because that’s what girls do, playing dress-up. The irony is that wardrobe and makeup are an integral part of any film. More than anything else, what characters wear and how they look is so connected to the heart of their character. Women were always allowed those domains because we know about clothes and makeup. But that’s exactly right, it’s why I think so many more women get to make short films, because there’s less money attached.

Follow the money, always. We can have every theoretical argument in the world that we want, but until there’s pay parity, it won’t change. My advice is always that if you’re a female practitioner in the industry, find out what the men are getting and go for that, and don’t accept anything less. It’s a bit like people say to me when I’m training my puppy, if you let her get away with something once, she’ll do it again. If you accept a lower pay rate than your male compatriot once, you’re perpetuating the problem, and you just can’t. You’ve got to say no, and it’s really hard, but you just have to. And the men have to say no, too.

This story is part of our month-long celebration of 40 years of NZ film. Follow all our daily coverage here