The Accountant 2: Should you really bring family into mercenary missions?

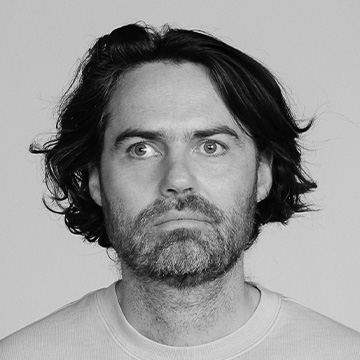

Ben Affleck returns as the titular butt-kicking bean-counter in The Accountant 2—with Jon Bernthal along for the ride as his brother. Rory Doherty bros down with the action thriller.

Quick survey: If you were a tactical genius and super smart detective, what is the likelihood that you’d invite your sibling on a high stakes mercenary mission? For Christian Wolff (Ben Affleck), the autistic mercenary and financial criminal who leads the Accountant series, there’s pros and cons. On the plus side, his brother Braxton (Jon Bernthal) is already a lethal assassin who travels the world taking out legions of criminals for high-rolling clients. The downside is that they’re not on good terms: Braxton only learned Christian was still alive at the end of 2016’s The Accountant, and his brother hasn’t been in touch at all in the eight years since their emotional reunion.

Both had a difficult upbringing: the severity of Christian’s autism pushed their military father to train his sons in martial arts around the world to teach them to be fearsome and self-reliant—mini-soldiers trained by a lone, paternal general. When Christian calls in Braxton to help solve the murder of the former Fed whose life Christian once spared (J.K. Simmons), the personality clash is off the charts: Christian is quietly, sternly worried about being on his little bro’s good side, but doesn’t understand that calling him in for a mission is a much more transactional relationship than the erratic Braxton deserves.

With its overt fish-out-of-water comedy, broad bro-ey sentimentality, and commitment to the ludicrous “autistic secret agent” world-building, The Accountant 2 is a thousand times more entertaining than its predecessor.

Affleck’s performance is, again, more dubious than authentic—a neurotypical actor adopting the brash affectations and stims of a neurodivergent person should always raise some eyebrows, but the heightened logic and language of an action movie makes the exploitative and inaccurate elements of Accountant films feel less offensive than manipulative prestige bait like Music, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close or the genuinely rank Rain Man. No-one is saying Affleck is “brave” for playing a neurodivergent character; if anything, the performance undermines the seriousness of the actor rather than the condition.

But Affleck’s deadpan comedy chops only entertain up until a point—watching The Accountant 2, any stretch of bromance banter or bursts of tactical action will be interrupted with the jarring realisation that, in this universe, neurological difference is either a superpower or an amusing caricature.

This is exacerbated when we learn that one of the film’s antagonists, the mysterious killer Anaïs (Daniella Pineda) got her skills via a rare neurological phenomenon, plus the time we spend with Christian’s remote handler, Justine (Allison Robertson). As a nonverbal autistic version of Batman’s Barbara Gordon/Oracle, she leads a unit of tech-savvy neurodivergent teens who act as Christian’s digital “eyes in the sky”. The Accountant 2 spends so much time detailing how exceptional and powerful autism can make you that it neglects to show any autistic people with normal, fulfilling lives; The Accountant 2 is an extremely odd counterpoint to RFK Jr’s ableist anti-autistic rhetoric in the United States right now.

All this to say: thank god for Jon Bernthal. He brings a sparky and arresting screen presence to Braxton’s expanded role, and his emotionally inarticulate brother is a sounding board to coax out more expressive, reactive, and frustrated energy.

There is a tired, confused thriller plot: it concerns women and children trafficked across the Mexican-American border and leads to a child rescue mission that shares some troubling connective tissue with the exploitation cinema-influenced Christian polemic Sound of Freedom, and the fact that Braxton is an abrasive, uncompromising murderer-for-hire drives Treasury agent Marybeth Medina (Cynthia Addai-Robinson) to ditch the criminal brothers and try to solve the mystery through legal means. But the relationship drama coursing through The Accountant 2 is effective: these are two brothers who have learned to cope on their own, and struggle to reconnect without letting resentment or reluctance take over.

The Accountant 2 taps into the amplified friction and catharsis of action movies that link up family members on a heist, mission, or hit: the family drama becomes intertwined with the action spectacle, a strange expression of our characters’ cohesion or disunity. On multiple levels, the audience is rooting for them to lock in, confront whatever’s holding them back, and do something miraculous and cathartic.

In Fast & Furious, Dom (Vin Diesel) is reluctant to let his family get in the way of danger, but by the time cars are dragging bank vaults through the streets of Rio de Janeiro, everybody counts as family and can join in on the stunts and heists. In Soderbergh’s Southern caper Logan Lucky, our hillbilly crime brothers (Adam Driver and Channing Tatum) have an unspoken, assumed loyalty that sets them up for NASCAR robbing success.

Terminator 2 and The Incredibles take advantage of the dysfunction of an action hero family learning to respect one another, but by featuring parent-child dynamics, they have a stronger sense of authority and guidance than the bank-robbing brother films Ambulance and Hell or High Water, which end disastrously for the more dysfunctional, unpredictable sibling in the relationship. On this front, The Accountant 2 has them all beat: the assault rifle-filled action film embraces the sensitivity of the brothers at the centre of the film, letting them lash out and make mistakes as they try to find the language to show each other they care, and they’re not running out on each other again.